|

Crate Expectations Building Westfield's Lotus 11 replica BY PETER EGAN PHOTOS BY THE AUTHOR |

Most test cars arrive at our palatial Newport Beach offices in one of two ways. Either the manufacturer drops the car off on our doorstep or we go to the manufacturer's distribution center and pick up the car ourselves.

Blame for this sudden madness can be placed squarely on the shoulders of three people. First, the late and brilliant Colin Chapman, who in the mid-Fifties designed a lovely aerodynamic sports racing car called the Lotus 11. The second guilty party is an Englishman named Chris Smith, whose Westmidlands firm has long specialized in the restoration of vintage Lotus racing cars. It dawned on Smith that it would be just about as easy to build an entirely new Lotus 11 from the ground up as to restore some of the bent and rusted iron that came through the front door of his shop, so he set up production facilities to produce a Lotus 11 replica known as a Westfield. The third culpable individual is R& T's own English correspondent Doug Nye (curse these clever Englishmen) who wrote a glowing report about the Westfield sports car for our June 1983 issue and gave all of us a vicious dose of the dreaded English Sports Car Lust, a disease many believed had been eradicated by modern technology.

In other words, after reading Doug's article on the Westfield car, we all wanted one. Being eyeball deep in canceled checks from my Lotus 7 restoration project (talk about bent and rusted iron), I decided the cheapest solution to this craving was to convince the Good Editor, the Beneficent Publisher and the Kindly Business Manager that what this magazine needed was a really good kit car, to be assembled as a magazine project. It worked.

The very words "kit car," of course, may be enough to send shivers of dread up and down the spine of the average hard-core car enthusiast. They conjure up immediate images of a disreputable parody of some nice old British roadster tamed up with too much upholstery, fake louvers, the wrong steering wheel, phony exhaust plumbing, a picnic basket where the engine should be and a tell-tale set of Volkswagen mufflers whistling from beneath the rear deck. There are a few nicely done kit cars around, but most tend to misinterpret the spirit of the original classic, or cost more than the real thing. Or both.

In reading Doug Nye's report, however, a picture emerged of a nicely crafted, eminently affordable kit that stuck very close to the original design and avoided many of the usual replicar pitfalls. With its tubular steel space frame and riveted aluminum chassis panels, the Westfield is very close in design to the original 11. It differs only in the use of fiberglass for the upper body panels (molds lifted from the original Lotus aluminum), heavier-duty tubing and a few extra braces in the frame to handle the rigors of street and pothole, and a slightly lengthened cockpit section to accommodate tall drivers and the Sprite driveshaft.

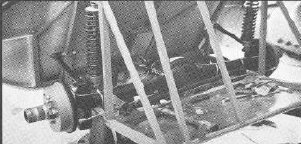

Though various engines can be adapted, the basic Westfield kit is designed around that widely available junkyard phenomenon, the drivetrain from a rusted-out Sprite or Midget, preferably the 1275-cc version. A live rear axle, also Sprite, is located by a Panhard rod and four trailing links. The front suspension uses Spridget spindles, steering rack, hubs and disc brakes, but the suspension pieces are fabricated Lotus-like from steel tube. As on the original 11 (and 7) the front anti-roll bar doubles as the front half of the upper A-arm. Coil springs and adjustable Spax tubular shocks are used front and rear.

Like most early Lotus cars, the 11 was always available in kit form with a variety of proprietary engines, so a modern-day kit seems like an extension of-rather than an affront to-tradition. The Le Mans model was powered by the 1100 Climax engine and had De Dion rear suspension, but the more affordable Club model used a live rear axle, and the still cheaper Sports version used alive rear axle with the inexpensive side-valve Ford 100E engine. The original 11 also came either with or without the aerodynamic hump behind the driver, and Chris Smith offers the Westfield in both body styles.

The U. S. distributor for Westfield is Rev-Pro Engineering Inc in Sarasota, Florida, another restoration and racing fabrication shop, owned by a very helpful gentleman named Willard Howe. Rev-Pro (6223 S. McIntosh Rd, Sarasota, Fla. 33583; 813 922--7371) sells the cars in full or partial kits, or as completely assembled vehicles, depending upon the customers wishes and checking account. All mechanical components are reconditioned. Prices range from $4600 for a basic chassis kit sans running gear and other Sprite pieces, up to $10,500 for a fully assembled car. At the time we decided to go ahead with the project, all Rev-Pro's cars were spoken for, so we called Chris Smith in England and found that he had an unsold left-hand-drive car with blue upholstery nearly completed on the assembly line.

By the time we ordered the car 1 had already tracked down a really clapped-out 1971 MG Midget ($ 400, with crash damage and no discernible oil pressure) that I planned to rebuild for our drivetrain. Chris Smith informed us, however, that his price for a freshly rebuilt engine, transmission and rear axle was only $1 100. That was less than it would have cost to buy and rebuild the innards of the $400 Midget, so we ordered the complete kit for a total cost of $7100. We requested the car be airfreighted, as I hoped to have it built in time to drive to the June Sprints at Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin. If you think it's expensive to airmail a Christmas card to your aunt in London, try sending a car. The postage figure is best left unmentioned. Take our advice and let Willard Howe get you one by boat. Have patience and it shall make you rich.

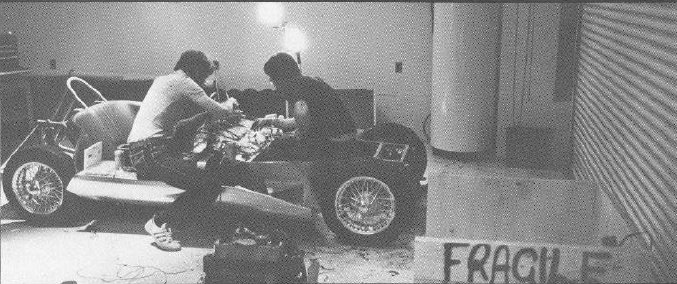

Very seldom does a test car arrive completely disassembled on three separate forklift pallets in the back of an airfreight delivery truck. Equally seldom does half the staff stay well past quitting time on a Friday night to greet a car and lift its various and weighty components from the back of that same truck (yes, we have no forklift). In fact, these things have never happened at all, until recently.

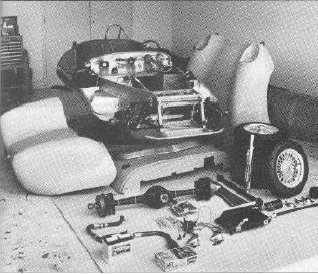

Three weeks after placing our order, the car was at the door. The Westfield actually arrived as three separate shipments; one for the chassis parts, one for the 1965 MG Midget engine and transmission, and the last containing the rear axle assembly. The largest pallet, of course, carried the chassis and primer-gray fiberglass bodyshell. This arrived covered with plastic wrap, criss-crossed with yellow tape reading "FRAGILE" and filled to the gunwales with random Westfield parts.

Unloading the pieces from the chassis tub was about as close to Christmas morning as anything I've experienced since the earlier part of my arrested childhood. The driver's and passenger's footwells were filled with items such as red Maserati air horns, carefully wrapped plexiglass windshield pieces, throttle and choke cables, exhaust header, red leather-covered steering wheel, a BSA motorcycle muffler, hood latches, bags of nuts and bolts and other pieces whose mysterious functions became clear only as assembly progressed.

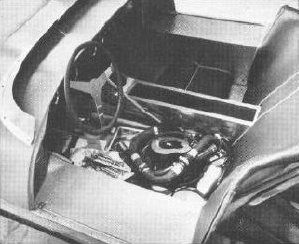

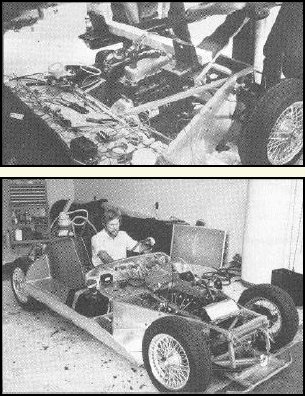

I was surprised at the completeness and finish of the chassis when we got the miscellaneous parts cleared away. The basic chassis arrived fully painted and upholstered, with the dash (instruments mounted) and all the aluminum panels riveted in place. The front suspension was bolted loosely together, and the pedal assembly, steering rack and column were fitted. The engine, transmission, rear axle and brakes were all clean, freshly painted and-from all appearances-thoroughly reconditioned.

Not one printed word of instructional material was included with the kit. but unless you're the sort of person who accidentally bolts exhaust headers to the rear axle, the relative position of parts is pretty self-evident. The Westfield is basic automobile at its best.

I decided the most logical progression was to get the car on its wheels with the brakes hooked up, install the wiring harness, slide in the engine, transmission and cooling system and get the car driveable before dealing with the bodywork and cosmetics.

Assembly of the rear suspension is reasonably easy. You center the rear axle in the frame and then shim the trailing links with washers so they move freely with the axle in its proper location. With the axle shimmed the Panhard rod drops right into place and the handbrake assembly can be hooked up. Front suspension, as mentioned, was already bolted loosely together, but there was more involved than just tightening down the bolts. Because of differences in manufacturing tolerances and weld thicknesses, some of the suspension bolts were too short for correct bedding of the locking rings in the Ny-lok nuts, so I did a bit of juggling with washers and bolts, filing the surfaces and substituting with bolts from my own massive and motley collection of project leftovers (the Westfield now has a grade-8 Lola trailing link bolt holding its left lower A-arm in place).

In the never-assume-anything school of auto mechanics, I took out all the factory-assembled nuts and bolts, to inspect and reassemble them with thread locking compound. If you aren't in a hurry to get the car ready for a trip to Elkhart Lake, it is probably also a good idea to drill and safety wire some of the more crucial suspension bolts. I didn't, however, and nothing loosened up after the car was assembled and driven.

Assembling the brake system was time-consuming because the flare fittings were new and unbedded and they all leaked after the initial tightening. Some sealed after considerable lessening and retightening, and others needed burrs touched up with light emery paper. The front calipers have double pistons and were very difficult to bleed because air wants to stay trapped in them. The calipers had to be removed from the spindles and rotated at various odd angles during bleeding (with a steel spacer between the pads) to get the air out. Even now, the pedal is not quite as hard as it should be, and I suspect there's a renegade bubble in there somewhere.

I greased the hub splines and mounted the brand-new 14-in. MGB wire wheels and Ceat Veltro radials, tightened the knockoffs down with a lead hammer and lowered the car to the ground. A roller.

At the time our kit was shipped, Westfield had not completed production of its wiring looms, and part of the deal was you had to fabricate all your own wiring. Chris Smith knew we were short on time, so he kindly tossed in a stock wiring loom out of a late model MG Midget. I spent two nights going blind on wiring diagrams and trying to track down wires that led to nonexistent 4-way flashers and seatbelt buzzers before throwing the MG wiring loom at a nearby stack of empty beer cans and cigarette butts. I called two friends, John Jaeger and Roger Salter, both of whom have restored many old British cars and profess actually to like making up wiring looms. (Too much Guinness. Or not enough.) At any rate, they're very good at it and fabricated a beautiful harness while I used the R&T floor hoist and a chain to drop in the engine and transmission. The drivetrain went in effortlessly, once I put the motor mounts in right-side up.

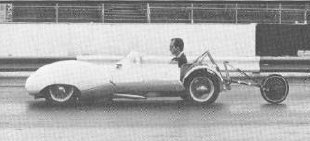

I adjusted the valves, installed the distributor, set the static timing, added oil, hooked up the battery, cranked the engine for oil pressure (70 psi cold), installed the plugs and twisted the key. The engine fired immediately, settling down to a smooth, mellow idle through the BSA bike muffler. I took the car out for a midnight drive and the throttle immediately stuck wide open (minor adjustment). Otherwise the car ran, felt and sounded beautiful. Without the weight of the bodywork it felt like a go kart and accelerated like hell, almost leaping down the road under bursts of acceleration.

In its standard position, the clutch pedal had too little travel to fully disengage the clutch, so I got my welder and made an adjustable pushrod for the clutch master cylinder. Those with shorter legs could accomplish the same thing by moving the entire pedal cluster closer to the driver by drilling a few holes in the pedal support bracket.

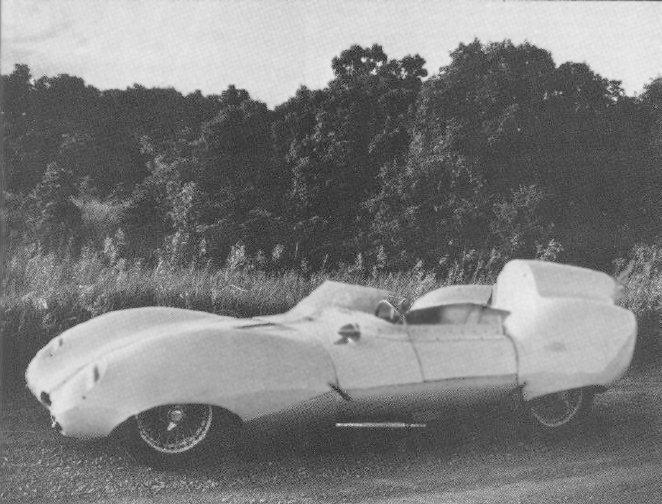

We sent the bodywork out to a paint shop while the fine mechanical details were being looked after. I've painted at least a dozen cars myself and now have lungs I imagine to be about two thirds filled with Bondo, primer dust and paint spray, so I prefer to farm it out these days. We chose a soft white paint with a medium blue racing stripe down the middle of the car. The color was chosen partly for tradition, because R&T had a Lotus 11 in American racing colors on the cover of the March 1957 issue when we first tested the car. The other reason was because the fiberglass on the Westfield is a bit bumpy and cobby and reflects fewer of its flaws in a lighter color. A dark green, for instance, would demand a lot of sanding and preparation.

The final project was to install the windshield, doors, side windows, headlights and covers. Most of these pieces come undrilled, so careful positioning is required to make everything fit before the holes are drilled. The kit provides polished brass nuts and bolts for windshield attachment, which add a nice finishing touch. The headlight covers needed some moderate shaping on a belt sander to fit their recessed openings, and the quartz-halogen headlamps provided were too long for the headlight buckets, so we installed a pair of smaller 6-in. motorcycle headlamps under the covers. The lights and all the wiring worked, the horn honked, and the car was done.

As kit cars go, I would say the Westfield has just about the right balance. It is not so thoroughly pre-assembled that anyone can just slap it together with acceptable results, nor is it so difficult that someone with reasonable mechanical skills and a good set of tools-and plenty of spare bolts and washers-can't produce a pleasing, well finished car: That, of course, is the appeal of a kit car. No two will come out quite the same, and the car becomes an expression of the builder's patience, craftsmanship and vision. The Westfield is a sound, well designed car that holds no unpleasant surprises for its constructor, but demands just enough careful massaging and detailing to make the construction process interesting and personal. When you're done, you feel as though you own this car in a way no one else can.

Working nights and weekends, I was able to finish the project in just over three weeks with a little help from my friends. That, of course, does not include the sanding and painting of the fiberglass bodyshell, which was done by a paint shop to the tune of $600. So with the cost of our kit, the paint work, and random nuts, bolts, fittings, fluids, wire and tape, the total cost of the car (excluding airfreight) was well under $8000. Expensive, but not bad these days for a new sports car, and cheaper than many other kits and replicas on the market. A buyer could save money, of course, by purchasing the basic chassis kit and then hunting down his own drivetrain, instruments and ancillary items.

How does the car work? Just fine, thank you. It's quick, light, fun to drive, and handles so well you can't believe the suspension was designed nearly 30 years ago. (But then the man who designed it was good at this sort of thing.) Suffice it to say that when the sun is just rising on a Sunday morning and you just happen to own a cap and a pair of goggles, the Westfield is not a bad thing to have lurking in your garage.

Follow-on R&T article: Northeast by Westfield