SOUTH OF AMBOY, California, the Mojave Desert is not really sports

car country. It looks like a good place for an A-bomb test or

a Sabre-Jet attack on a giant mutant spider. It is mirage country,

where everything shimmers in the distance, and you cross the white

and dazzling salt flats of Bristol Dry Lake half expecting T.E.

Lawrence to come riding out of the heat waves. The roads through

this territory run straight as the crow flies, only it's too hot

for crows and there's nothing for them to drink so there aren't

any.

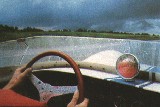

There aren't many open British sports cars, either. In fact we

were nearly alone on the highway, which on an afternoon in early

June was positively humming with heat. My wife Barbara and I were

on our way to Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin. We were cruising across

the Great American Desert in a small English car, designed a quarter

of a century ago to run on narrow green lanes and mist shrouded

race tracks in a country where sunlight is about as common as

a lunar eclipse. I was behind the wheel, watching the water temperature

gauge with one eye and trying to remember if there was any place

in England where you could drive upgrade all day in 110-degree

weather. I didn't think there was.

This particular English sports car was a Westfield. The Westfield

is a replica of a Lotus Eleven, a very successful sports racing

car from the late Fifties and one of the cars that made Colin

Chapman a household name in households that love fast, agile,

nice-looking cars. Just three weeks prior to our trip, the Westfield

had arrived on Road & Track's doorstep as a disassembled,

unpainted kit. Driven by some kind of tangential homing instinct,

I'd spent all of my nights and weekends virtually living in the

R&T garage, subsisting on a health fad diet of Coke and cigarettes,

trying to assemble the car in time to make the June Sprints.

No Midwesterner, fallen-away or otherwise, likes to miss the Sprints,

which is an annual rites of spring tradition held at what may

be the most beautiful sports car track in the country. The event

is half SCCA National and half medieval festival, drawing a huge

number of entrants from all over the country. An added incentive,

if we needed any, was that our friends Chris Beebe and crew would

be racing his D-Production Lotus Super Seven.

The night before we left on this grand trip I was still working

on the car (proof that work expands to fill the time allotted)

when our Editor Emeritus, Tony Hogg, stepped into the lighted

chaos of the R&T garage. Tony was especially interested in

the project because he had owned and raced an Eleven in England

and Europe during the late Fifties. Tony lit a cigarette and asked

how things were going. Pieces of the car were still scattered

all over the floor.

"Almost finished," I said. "The car has to be ready

to go tonight because Barb and I are leaving for Elkhart in the

morning."

Tony raised one incredulous eyebrow. "You're driving that

bloody thing all the way to Elkhart Lake?"

"Yes," I said. "It's going to be sort of a motorcycle

trip on four wheels. The Westfield doesn't have a full windscreen

and the convertible top isn't in production yet, so we're taking

rainsuits and helmets. It'll be interesting," I added, "to

see how an open sports racer works as a cross-country touring

car."

Tony gazed at the Westfield for a few moments and took a thoughtful

drag on his cigarette. "I should think," he said in

his best detached British way, "that it'll be just bloody

awful."

Awful, of course, was a matter of perspective. Barb and I had

crossed the country a half-dozen times on various motorcycles,

so the prospect of leaning back in a comfortable seat, largely

protected from the wind, seemed relatively luxurious. The Westfield

also had more luggage space than most motorcycles. There was storage

space on the wide armrest panels inside the doors and on the floor

beneath the arched knees of driver and passenger. The rear body

section swung upward, revealing a flat tray that was part of the

floor pan. This area was subject to dust and water spray from

the rear tires, but luggage could safely be wrapped in plastic

garbage bags and lashed to the frame and spare tire. The Westfield

was not the Globemaster of cars, but we wouldn't have to leave

our toothbrushes behind.

The only slightly awful part was taking off on a 5000-mile journey

with an untested car, with virtually no time to run the engine

in. Adjustments would be made on the road. I packed enough tools

to field-strip the car if necessary and repair nearly anything

en route. Fortunately the Westfield is a very simple car held

together with only a few conventional sizes of nuts, bolts and

other fasteners, so the toolbox was small.

I finished the car at midnight, drove it back to our house and

packed what few clothes I needed. I told Barb we should get up

at 4:00 a.m. and leave in the early morning darkness to avoid

crossing the Mojave in the afternoon heat, so we set our alarm

and went to bed.

Getting up at 4:00 a.m. sounded like a much better idea at midnight

than it did when the alarm went off at 4:00 a.m. We went back

to sleep and eventually got up at 9:00 a.m. By 10:30 the car was

packed and we pulled out of the driveway into a clear, hot summer

morning; mad dogs and English car, off toward the noonday sun.

Part of the plan on this trip was to avoid Interstates at all

cost, so we crossed the California desert part way on Highway

62 and then turned north toward Amboy. This is all 2-lane blacktop

that runs through such oases as Yucca Valley, Twentynine Palms

and Essex, with miles of cactus, Joshua trees and empty desert

between.

By the time the freeways of greater and lesser L.A. had spilled

us onto these emptier roads, it occurred to me the Westfield had

a remarkably good highway ride for a taut, light sports car. Not

nearly as jittery as might be expected.

The added weight of our luggage no doubt helped, and the car cruised

serenely at 60 to 70 mph with a sort of hunkered-down bantamweight

Cadillac feel. A bit too hunkered down at times. Even with the

front springs jacked up all the way on their platforms, the lowslung

oil pan occasionally scuffed the pavement and random dead things.

Otherwise, the Westfield made a fine highway car. The side-mounted

BSA muffler gave out a lovely, throaty purr. Even at 75 mph the

cockpit was relatively tranquil. (Don't ask relative to what.

An N2S Stearman, maybe.) There was some backdraft on the passenger's

neck, but the headrest/fin did a remarkable job on calming the

air around the driver's head. In normal driving position you looked

over the windscreen rather than through it, but the plexiglass

deflected nearly all of the wind over your head. Stones and insects,

however, refused to follow the wind flow, so goggles or a helmet

with a face shield was nice, especially around gravel trucks.

Until about one o'clock in the afternoon the car ran perfectly,

with the water temperature needle centered on Normal. After that

the desert temperature climbed to just over 100 degrees and the

needle moved halfway to Hot. When we started a long upgrade climb

near Yucca Valley the needle pegged itself solidly on Hot. The

intense engine heat, aided by an exhaust header that wraps around

the front of the left footwell, also began to warm up the driver's

compartment. The pedals got hot and the handbrake lever began

to burn my leg, so I wrapped a sweatshirt around the handle. We

stopped at a country store, parked under a tree and got out to

cool down for a while.

I poured down a quart of Gatorade and raised the Westfield's hood

to look things over. I smelled gasoline and discovered that the

exhaust header heat was boiling fuel out of the float bowl on

the rear SU carb. Willard Howe, the U.S. Westfield importer, had

warned me this could happen on blistering hot days, so I had cut

a vent in the aluminum bodywork behind the carb to let the hot

air out. This, obviously, was still not enough. The Westfield

was a brand-new car, untested in this climate and being driven

on a true shakedown run, so I began a list of small improvements

and modifications to be made when we got to Chris Beebe's shop

in Wisconsin. I got out a notebook and wrote: " 1. Asbestos

heat shield for driver's footwell. 2. Improve heat shield between

carbs and header. 3. Make cold air duct for carbs. 4. Move radiator

into nose with full shrouding and fit electric fan."

I poured some cool water on the carbs and we took off: climbing

and warming our way over the Bullion Mountains and down onto the

flats of Bristol Dry Lake.

"What are you spraying for?"

"Roaches."

"Talk about service," I said when the man was gone.

"You won't find roach spray much fresher than that."

We filled our almost-empty fuel tank and calculated our mileage

at 44 mpg. Not bad for a fast car with a new engine. The tank

held only 5 gal., but with that mileage we didn't have to start

looking for gas stations much before 160 miles. The Westfield's

small frontal area and aerodynamic shape certainly didn't hurt

its fuel economy: at highway speeds the car felt almost as if

it were traveling through a vacuum, and its ease of acceleration

at passing speed added to the sensation. With the big MGB wire

wheels and the standard 4.20:1 Sprite rear end, the engine was

turning a fairly relaxed 3700 rpm at 60 mph.

We passed through Essex, California (pop. 150); one of those places

that makes Paris look like a huge glamorous city near a nice cool

river. A sign on a building said, "Thanks to Johnny Carson,

Essex has TV!" I figured there was a story there somewhere,

but it was too hot to stop and ask.

Turning onto the inevitable Interstate long enough to get ourselves

out of California, we headed down I-40 toward the green banks

of the Colorado River, past the rock spires of Needles.

On the Interstate the Westfield attracted an incredible amount

of attention. People rolled down their windows to ask what it

was, elderly couples smiled and waved and a Bible school bus listed

to one side as all the children ran to the windows. Cars followed,

passed, dropped back and followed again to get a better look,

and people going the other way on the Interstate actually honked

and waved from across the median. Wherever we stopped, the Westfield

created a minor interrogatory riot.

Nearly everyone asked (1) what kind of car it was, (2) what kind

of engine was in there, (3) was the engine in the front or the

back, (4) how much did it cost, (5) what kind of mileage did we

get, (6) where were we going to and coming from. and (7) what

were we going to do when (not if) it rained. A few fully grown

people asked if they could just please sit in it for a minute.

At a gas station I helped a husky, sunburned 50-year-old farmer

in overalls slide down into the passenger seat. He looked around

himself and said to his wife, "Now this is all right."

I felt as though we were barnstorming the first airplane across

the country. I think we could have charged money for rides. The

car had some elusive magic of shape and scale that stirred the

imagination.

We passed through Kingman and late in the afternoon began climbing

into the cool green Arizona mountains. After a day in the desert

the pine country of the Prescott National Forest was like an-other

planet. Just after sundown we swerved to avoid three deer crossing

the highway and decided the nearby town of Williams would be a

good place to stop for the night. We checked into a motel, covered

the car and walked off in search of a stiff drink.

In the morning I got up early to retorque the cylinder head and

adjust the valves on our green engine. An Australian gentleman

walked out of his motel room and said, "Ha! A Lotus Eleven!

With the car cover on in the dark last night I told my wife it

was a D-Type Jaguar. Nice car, either way."

We stopped for fuel and the kid at the gas station walked around

the car, obviously looking for an emblem or some sort of make

identification. He finally got down and read the word engraved

in the knock-off hubs, and I saw him mouth the word, "UNDO."

I thought for a moment he was going to ask the classic question,

"What year Undo is that, mister?" Alas, people are more

sophisticated these days, and in the end he asked, in his best

Steve Martin imitation, "Now what kind of a dang deal is

that?"

Barb took the first stint at the wheel and we headed up to the

Grand Canyon in clear, cool morning weather. The car was running

beautifully. When we entered the National Park. people seemed

to be leaving in droves, but we were almost alone going in. I

hypothesized that Editor John Dinkel was holding court at the

Main Lodge, telling his favorite puns. We drove to the rim of

the Grand Canyon and I tried to stifle my usual pathetic reaction

to the wonders of nature, in which I lament at having the wrong

camera lens. Barb said, "I wonder what the Indians thought

when they first of t walked up to the edge of this canyon."

'Probably, `Wait'll the white man sees this. The eviction notice

is practically in the mail.' "

On the winding road out of the park we came up behind our nemesis,

a parade of big dumb lumbering motorhomes. I noted with interest

that these things all have names to suggest speed and grace, like

Flying Arrow, Golden Eagle and Apache Brave.

We passed through the Hopi Indian Reservation and the beautiful

red pastel rock formations of the Painted Desert, which was almost

as hot as the Mojave Desert but slightly dustier. The heat in

the Westfield's footwell at noon was astounding. I considered

stopping at a supermarket and propping a frozen turkey against

the gas pedal. That way my feet would stay cool and dinner would

be ready by the time we got to Durango.

Just across the Colorado border we pulled into the town of Cortez

right on the tail of a huge parade passing down Main Street. It

was Frontier Days or Yahoo Centennial Days or something. We passed

through just after the parade, and the street was still lined

with people, several of whom were sober. We drove down a 3-mile

gauntlet of whistling and shouting citizens. Most, I'm sure, thought

we were part of the parade, a late entry. We smiled and waved

at everyone, and Barb said, "I wonder if I should sit on

the back deck of the car and blow kisses."

I looked at some cowboys who had just staggered out of a bar and

said, "Better you than me." We crawled through town

and emerged on the other end with the temperature gauge pegged,

inhaling vapors of hot horse apples sizzling on an overheated

Austin sump.

Climbing back into the Colorado Rockies, we made it to the old

mining town of Durango by sunset and checked into the beautifully

restored old Strater Hotel. We put our luggage in the room, which

was done up in grand 19th Century style-hardwood wainscoting,

brass bed, stone pitcher and bowl, etc. - and went out for a Mexican

dinner. We came back later and watched The Thing on our 19th Century

color TV

After an early Sunday morning start into a cool, slightly misty

day we stopped in Pagosa Springs for breakfast at a Main Street

cafe. As we sat drinking coffee, the cafe's clientele defected

en masse to the sidewalk for a look at the Westfield. The lady

at the cash register said, "I hope you folks aren't too hungry

for your bacon and eggs. That's the cook out front lookin' at

your car."

People driving home from church were double-parking their cars

and pickups, jumping out in their Sunday best suits and cowboy

boots to look at the car. We went out and joined the throng.

It was hard to know what to call the car when people asked. Westfield/Lotus

Eleven was a little unwieldy, so we usually picked one or the

other and said it was made in England. The engine was another

problem. If you told people it had an MG engine, they'd whistle

and say, "Whoo-eee! I bet that thing really flies!"

If you admitted it was an MG Midget engine, they'd say things

like, "Ha! Probably smaller than my kid's Suzuki dirt bike

engine. Bet she gets good mileage, though." Caught off guard,

we found ourselves describing it, variously, as an MG, MG Midget,

1275 MG Midget, Austin, Austin A-series 1275, Austin-Healey, Sprite

or BMC engine. For the sake of consistency, Barb and I collaborated

halfway through the trip and agreed to call it an Austin Healey

engine, as that seemed to provoke the loudest murmurs of approval.

East of Del Norte we cruised steadily downhill through an ever-widening

valley and I had the feeling we were about to be spit out of the

mountains of the gold- and silver-mining West onto the prairie

and cattle ranch West. The car was humming along perfectly and

it was still spring in the mountains. The cottonwoods and aspens

had that lacy green look and the meadows were in bloom. It was

odd, here and there, to see rustic old ranch houses with gigantic

parabolic TV receivers in their front yards, like an Eighties

update of Gene Autry and the Radio Ranch. It looked all wrong.

Near Monte Vista we hit a dust storm that looked from a distance

like a moving river of fog about 600 ft high. We drove into it

to find big pieces of thing blowing across the road, mingled in

with the stinging sand. Tumbleweeds went by so fast they weren't

even tumbling. We passed an outdoor movie theater and 1 explained

to Barb that in order to hit the screen the projectionist would

have to aim 20 ft to the left to correct for wind. "And on

a bad night," I added. "the movie ends up in Kansas."

The river of sand died away so we took our helmets off and put

our caps and sunglasses back on. It was more pleasant to drive without helmets, so we reserved these for rain and gravel storms.

Highway 50 took us into Kansas, following the green willows and

pretty towns along the Arkansas River. I'd been through only the

corners of Kansas before, so most of my preconceived notions of

the state were based on the opening moments of The Wizard of Oz,

with its flat, sepia-toned landscape and evil tornadoes. In the

early summer, at least, the Kansas we saw was a farmland of rolling

green contours interspersed with small towns that radiate a wonderful

quality of permanence and dignity. Our route across Kansas was

one of the most beautiful parts of the trip.

The presence of evil tornadoes, however, is no myth. We stopped

for lunch in Jetmore, Kansas and noticed some very dark thunderheads

building up in the northwest. I asked a farmer at the cafe if

tornado season was over and he said, "hope. Just getting

into full swing." As we left town a yellow biplane crop-duster

swept across the highway in front of us, flying against a backdrop

of dark clouds and distant pitchfork lightning. Hitchcock would

have loved it.

I looked around at the sky and thought, this, by God, is real

weather. Not like in California where it just kind of creeps in

and sits on you. In Kansas you watch the weather at work around

you like some kind of big unpredictable machine where thunderheads

and shifting winds are the moving parts. Advancing clouds have

a relentless quality; you can look around the broad horizon and

see several storms developing at once.

Unlike the mountains. where you are often locked into a single

route of travel, the plains are mapped out in a great grid of

highways, so by zigzagging across the state you can play checkers

with the weather and miss the worst storms. As in checkers, of

course, sometimes the weather jumps you and wins. And in Kansas,

sometimes the weather comes along and blows all the checkers right

off the table.

At five o'clock in the afternoon we ran out of zigzag options

and found our-selves in the middle of a blinding thunderstorm

illuminated by tree-ripping lightning bolts. It hit us so hard

and doused us so completely we didn't bother to get out any rain

gear. I just put my foot in it and headed to the closest motel

in Junction City. There we turned our room into a vast drying

rack for clothes, sleeping bags and tools from my water-filled

toolbox. In heavy rain, it turned out, the rear tires churned

great quantities of rainwater up into the rear bodyshell. so that

it ran down our seatbacks like a waterfall and filled the car.

I added, "5. Needs inner fender wells" to my improvement

list.

The morning after the storm was cool and clean with a sky the

color of morning glories. Willard Scott, on our motel TV, said

there'd been 25 tornadoes in the plains states the previous day,

with more on the way. As we headed across the Missouri River,

however, there wasn't a cloud in the sky.

Northern Missouri was our first exposure on the trip to real sports

car country. Narrow winding roads, hills and steep valleys, 1-lane

bridges and trees forming a tunnel of shade over the road.

It was also the most dangerous section, because farmers with tractors

and manure spreaders were not ready for us. Nothing in their lives

had prepared them for the specter of a small white bomb of a car

with blue racing stripes to come drifting around a blind corner

or bearing down at high closing speeds. We weren't driving too

fast for the Westfield; just too fast for pickup trucks and hay

wagons with a relaxed indifference to the centerline. After a

few close calls we decided to slow down and live to enjoy the

scenery. The Westfield was in its element, running cool and handling

the road flat and quick as a go kart.

On Highway 6 1 saw a sign for a place called Novinger and turned

off the road, down the town's main street. My parents had lived

in Novinger for a couple of years before I was born. My dad had

bought a small weekly paper there with his Navy savings at the

end of World War 11. 1'd heard so many stories of this little

coal mining town that it existed larger in my imagination than

the places I'd seen myself.

It turned out the coal mines are closed now and the only people

living in town are those who work elsewhere. We drove down a ghost

town main street of dusty, boarded-up storefronts, peeling paint

and faded signs. It looked like the town where Bonnie and Clyde

tried to rob the bank and found it closed. A heavy-set young man

with, believe it or not, a Mohawk under his seed cap and a T-shirt

listing Ten Excuses for Not Having Sex gave us a tour of Main

Street and pointed out where all the stores had been. He couldn't

remember a newspaper office ever having been in the town. We stopped

for a drink in the one open bar, and no one in there remembered

either. Novinger was like a lot of country towns we passed through.

It was a little too small to support commerce, so people just

gave up on the idea of having a town and quietly moved away. What

remained was a house collection, with bar.

Driving into southern Iowa at sunset; we passed a slow semi on

a long hill. I casually looked up at the driver as we passed and

was greeted with a blinding flash of light. As my vision recovered

I realized the driver was grinning and waving a small Instamatic

flash camera at us. He gave us the thumbs up sign and backed off

so we could pass. As we pulled ahead another flash was fired at

our backs. We drove into Ottumwa and found a motel with blue dots

all over it.

In the morning I checked the oil. It was down a half-quart, after

2000 miles of driving in hot weather. Our best mileage up to that

point had been 52 mpg (Kansas tailwind) and our worst had been

43 mpg (Colorado mountain headwind). None of the nuts and bolts

I checked had loosened up, and after five days the car was running

cool and strong. Valve clearances hadn't changed since Williams,

Arizona, and the plugs were a nice tan color. The points looked

good, timing was spot-on and the oil pressure was still at 55

psi hot. I'd left California fearing the Westfield night be a

slightly fragile, fussy sort of car on a long trip. Now, a few

hours from the Wisconsin border, I'd begun to think of it as a

remarkably tough, durable machine. Most of my constant listening,

checking and adjusting had been wasted effort. As we slid into

the car on the sixth and last day, it was like putting on a comfortable

pair of shoes. The sound of the engine starting on that clear

summer morning was pure music.

We crossed the Mississippi near Dubuque at mid-morning and headed

into the green Ozark-like hill country that is southwestern Wisconsin.

My growing up in that area has nothing to do with a personal opinion

that this is some of the most beautiful country on earth. It was

shaded valleys, rivers, red barns and villages all the way into

Madison. From there we drove the back roads to Elkhart Lake, passing

through pretty towns like Greenbush and Glenbuelah, and all of

a sudden we found ourselves braking and downshifting into the

city limits of Elkhart Lake, something I'd first done 18 years

ago in my green TR-3. We motored down the shaded village streets,

past the lawns and white porches of Siebkin's hotel and headed

south toward the gates of Road America.

On the seventh day the Westfield rested beside the track. Chris

Beebe and his Lotus Super Seven did all the work, winning the

D-production race in a hard-fought battle. About 30 of us who

like to celebrate such things retired to our traditional campground

on the shores of Lake Michigan, pitched tents. ate grilled bratwurst

and drank Bohemian Club, the official beer of southwestern Wisconsin

Lotus Seven owners and their ilk. In the morning all evidence

suggested we'd had a good time.

When the race weekend was over, Barb had to fly back to California

and her job, so Chris Beebe agreed to drive the Westfield back

across the country with me. Before leaving, we worked on the car

for three days at Chris's shop in Madison. We made a new heat

shield for the carbs, ducted air to them, moved the radiator forward

in the nose and added shrouding, bolted a piece of asbestos to

the driver's footwell, installed some inner fenders over the rear

wheels and jacked the front ride height up with taller springs.

(Several of these improvements have now been made by the Westfield

people.)

The return trip was pleasurable and uneventful, and we made the

2200 miles without having to lay a hand or wrench on the car.

Our small mechanical improvements worked wonders, eliminating

the Westfield's few irritants. The engine ran cool, the rear SU

no longer overheated, the footwell was incapable of roasting a

turkey and the oil pan didn't bottom on gum wrappers and lost

coins. Chris had a great time and said he hadn't seen people so

intrigued with a car since he and his father took a trip in an

XK-120 Jaguar in the early Fifties.

The best piece of road on our return route was a stretch in the

Colorado Rockies, 110 miles of mountain switchbacks and hairpins

between Montrose and Durango on Highway 550. When we pulled up

in front of our hotel in Durango, Chris said, "I've been

trying to think what car might have been more fun to drive on

a road like that, and I can't think of any."

I couldn't either. The Westfield had some of the oddball charm

of the TC Chris and I had driven to Road Atlanta the year before

(R&T, April 1983), but it was faster and the steering worked.

The racing car heritage, too, had an appeal. Looking over that

low windscreen at the sleek front bodyshell, sitting in a stark

aluminum interior and listening to the raspy exhaust note as you

downshifted into a corner, you needed a firm grasp on reality

to remind yourself that this was not the last Mille Miglia. A

helmeted passenger sitting next to you with a map on his knees

did little to dispel the image.

The Westfield was just outlandish enough that you didn't mind

any discomfort shed out. Other sports cars had become more civilized

by small degrees until they were so much like sedans that people

could no longer remember why they wanted a sports car in the first

place. No one, if he were honestly building a car for sport, would

load it down with carpets and courtesy lights and 40 pounds of

window-winding mechanism. Maybe, I suggested to Chris, sports

cars really are supposed to have nothing added that doesn't' make

them go fast, and every so many years someone has to rediscover

that. Like the people in England who make the Westfield.

When we got back to L.A. late on a Friday afternoon and finally

pulled into our driveway, we were neither relieved nor happy to

have the trip over. Tony Hogg, rest his soul, had been wrong when

he said the Westfield trip would be just bloody awful. He was

only kidding, of course. He had spoken mainly for effect, with

a glint of good humor in his eyes. Tony himself had been a true

enthusiast of everything automotive that is pure fun. He knew

better than anybody that driving an open sports car across America's

back roads in summer is further from being awful than nearly anything.

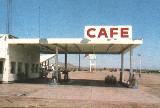

In Amboy we came across an inviting gas station with a willow

tree and a CAFE sign with red letters 12 ft high. A perfect place

for pulling off the desert. The cafe was cool, bright and polished

inside: lots of stainless steel coolers with that sweating, refrigerated

look. We had iced tea, soup and coffee with a side of ice water.

"This is a nice place," Barb said. I was nodding when

a man with a pressurized canister and nozzle asked us to move

our feet so he could spray the crack along the bottom of the counter.

In Amboy we came across an inviting gas station with a willow

tree and a CAFE sign with red letters 12 ft high. A perfect place

for pulling off the desert. The cafe was cool, bright and polished

inside: lots of stainless steel coolers with that sweating, refrigerated

look. We had iced tea, soup and coffee with a side of ice water.

"This is a nice place," Barb said. I was nodding when

a man with a pressurized canister and nozzle asked us to move

our feet so he could spray the crack along the bottom of the counter.

On the other side of Alamosa we passed a hitchhiker who was walking along the highway with his thumb out. He was so drunk that a gust of wind caused him to weave and totter into the road ahead of us. I swerved and narrowly missed hitting him. He was wearing a stars and stripes backpack, a great big felt

hat with a pheasant feather in the band, a fringed leather vest,

bellbottoms with decorative stitching at the cuffs, and he looked

about 48 years old, sun baked and hard as nails. One of those

unfortunate ramblin' alcoholics who's inherited all the unwanted

regalia of the not-so-recent past. I wondered what would happen

to him. It's a very long stagger to the next town anywhere in

eastern Colorado, and hard to get picked up when you're losing

a drunken battle with the wind.

On the other side of Alamosa we passed a hitchhiker who was walking along the highway with his thumb out. He was so drunk that a gust of wind caused him to weave and totter into the road ahead of us. I swerved and narrowly missed hitting him. He was wearing a stars and stripes backpack, a great big felt

hat with a pheasant feather in the band, a fringed leather vest,

bellbottoms with decorative stitching at the cuffs, and he looked

about 48 years old, sun baked and hard as nails. One of those

unfortunate ramblin' alcoholics who's inherited all the unwanted

regalia of the not-so-recent past. I wondered what would happen

to him. It's a very long stagger to the next town anywhere in

eastern Colorado, and hard to get picked up when you're losing

a drunken battle with the wind.